Why Crowd-Moderation Needs Support: Insights from Our Research

Governments and tech companies often call for users’ help in creating safe and inviting platforms. Whether it’s through built-in reporting buttons, community notes, or rating systems, these tools rely on the active and continuous involvement of social media users. But what happens when users are expected to take action?

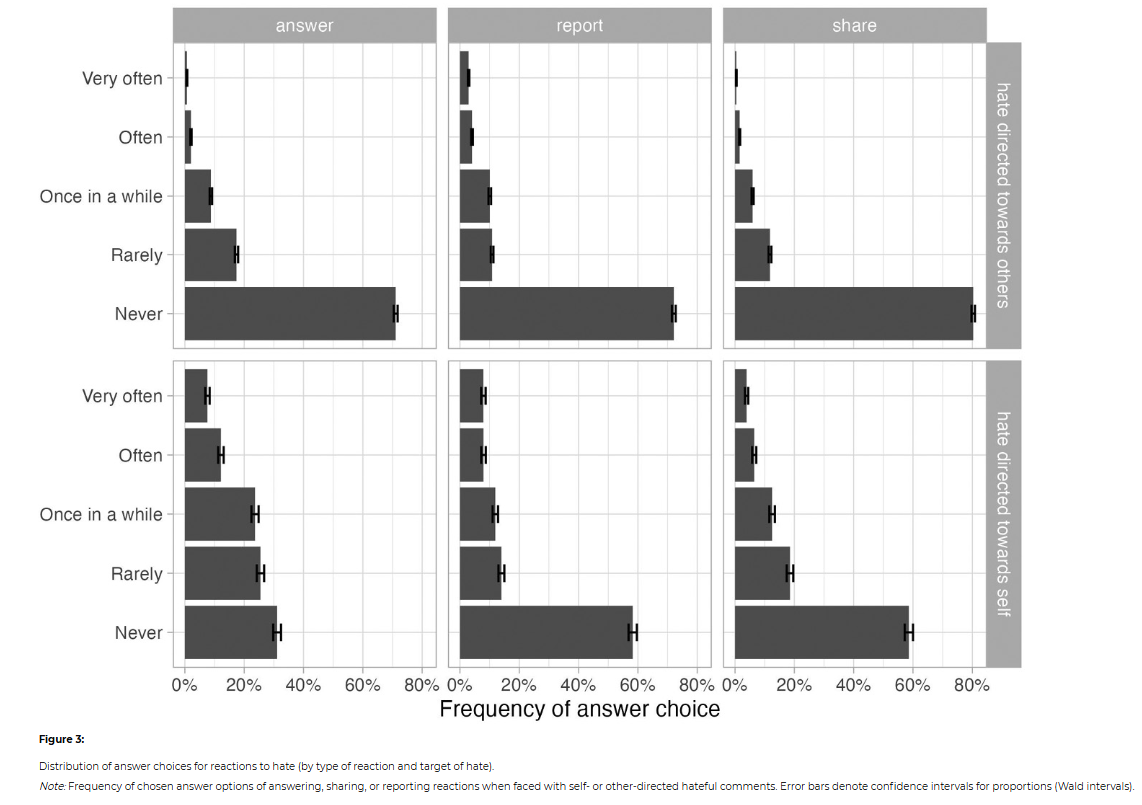

Our research into existing levels of individual bystander reactions reveals that crowd-moderation—where bystanders respond to online hostility they encounter in their daily online interactions—is unlikely to happen naturally. The reality is that bystander reactions are too few and far between to effectively support self-moderating platforms.

Our research

To explore whether crowd-moderation can be a viable moderation strategy, we surveyed almost 25,000 Danish social media users about their experiences with online hostility. Specifically, we examined how often people respond by reporting or replying when they encounter hostile content online. We also looked at whether reactions differed depending on whether the individual was a target or a witness and how experiencing online hostility impacted their emotional state and willingness to engage in future online debates.

We theorize that bystander reactions come at a cost for individuals and are thus naturally infrequent—especially when it comes to more costly actions like counterspeech. Our findings support this theory: Danish social media users rarely respond to online hostility targeting others, especially by replying (counterspeech). This indicates that crowd-moderation, as a spontaneous, organic response from users, may not be a reliable strategy for social media platforms.

Key takeaways

The Different Costs of Reactions

Replying (Counterspeech): Engaging in counterspeech is "costly" because it takes more effort and courage. It involves crafting a response and risking further hostility in return.

Reporting: Reporting harmful content is less "costly" because it’s a simple, private action that requires just a few clicks. It doesn’t expose the user to the same risks as counterspeech.

Witnessing Online Hostility is Troubling

Our data shows that most respondents experience negative emotions when witnessing online hate, and a majority report feeling a desire to withdraw from online discussions altogether.

The Target Matters

When You're the Target: Responding to hostility is more likely when the user is personally targeted. In these cases, responding can feel like an opportunity to stand up for oneself.

When You Witness Hostility Toward Others: Responses are far rarer when the user is merely a bystander, witnessing hostility directed at someone else.

Bystander Reactions Are Rare

Our data shows that a majority of respondents say they never respond (through reporting or counterspeech) to hate directed at others.

Crowd-Moderation as a Collective Action Problem

Crowd-moderation can be seen as a "lost" public good. For it to work, many users must voluntarily invest their time and effort to ensure that social media platforms remain positive spaces for discussion. Yet, any user can enjoy the platform without contributing to moderation efforts—whether through reporting or counterspeech.

The Need for Interventions

For bystanders to become part of the solution, we need to motivate them and demonstrate how small, individual actions—where users "stand up" instead of just "standing by"—can accumulate into meaningful and impactful results.